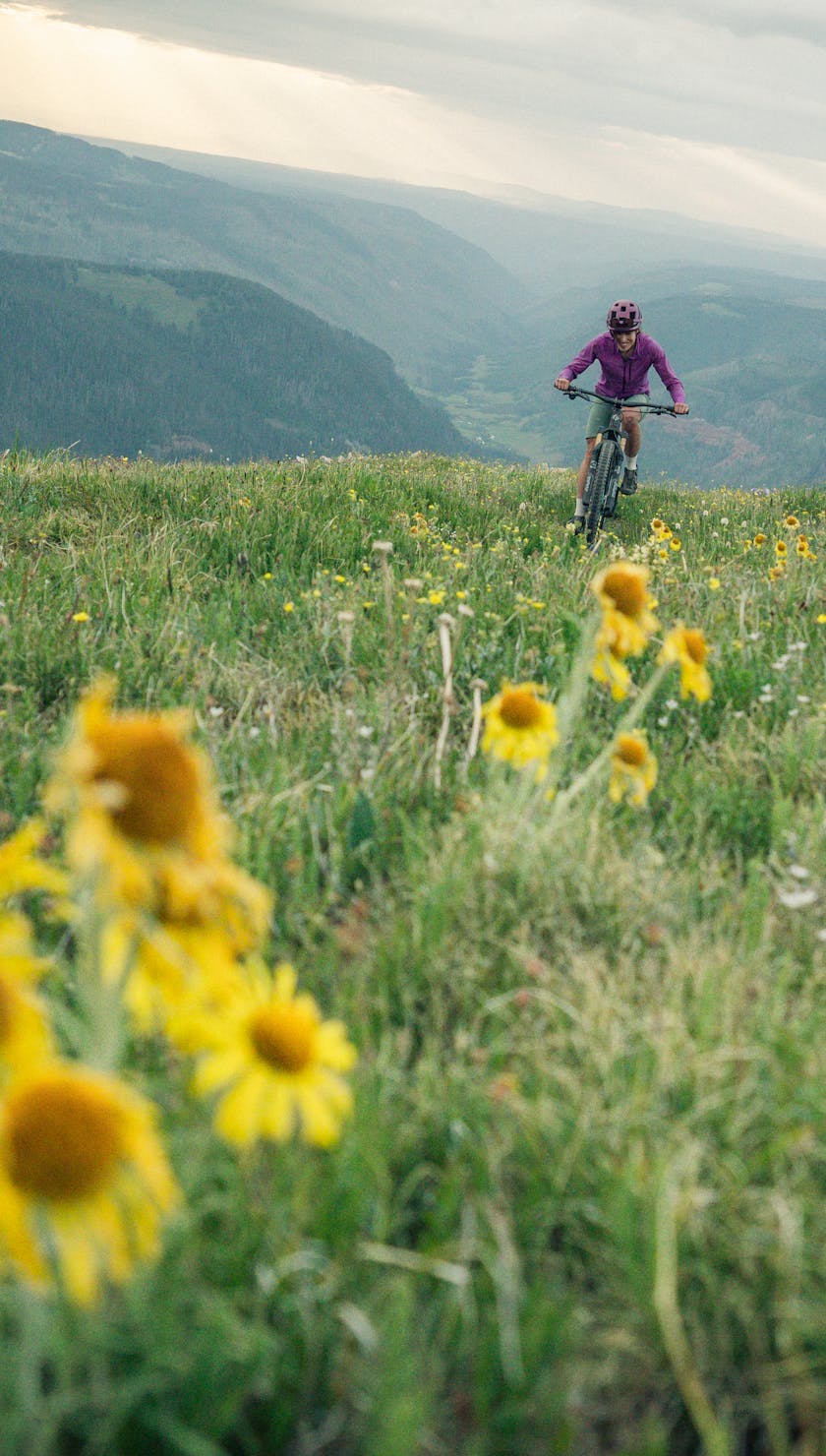

Ambassador Highlight - Nichole Baker

In the high country outside Salida, Colorado, Nichole Baker lined up for one of the hardest efforts of her life. The Vapor Trail 125 is seventeen hours of technical singletrack, relentless hike-a-bike, and long stretches of riding through the night. She knew it would push her well past her comfort zone. “There’s a hike-a-bike that’s thirty-seven minutes straight,” she says, “then on and off for almost an hour just before sunrise.”

Nichole devoted much of her year to preparing for this race – following a structured training plan and logging long days with strong riding partners back home in Durango. Just weeks before the start, she suffered a foot injury that, for most riders, would have meant not starting at all. Nichole took a different approach. Patient and realistic about the unknowns, she decided to see what her body could handle. Ultimately, she didn’t finish the race, but she pushed herself to her absolute limit – battling terrain and conditions that proved too much for the injury.

Despite her current commitment to training and racing, Nichole didn’t come to mountain biking chasing podiums. She found the sport almost by accident. At twenty-one, while working at the University of Michigan’s research center, she was looking for an outlet after an emotionally difficult chapter of her life.

“A couple of colleagues knew I was a runner and said, ‘You should try mountain biking,’” she recalls. They loaned her a steel hardtail and pointed her toward the Potawatomi Trail System outside Ann Arbor, Michigan. “It just clicked,” she says. “That first ride – I fell in love. It was hard and humbling and exactly what I needed.”

From that day forward, riding became central to her life. She’d often embark on 4 a.m. rides to squeeze in miles before early hospital shifts. The rides became her daily ritual, but Michigan’s flat terrain and limited trail access left her wanting more. “The idea that I could ride out my door every day felt like a dream,” she says.

In 2012, a hospital job posting in Durango caught her attention. She’d never been to southwestern Colorado, but a few Google searches and a YouTube rabbit hole were enough. “I remember watching people descend Kennebec Pass and thinking, ‘That’s it. That’s where I want to be.’” She packed up and drove west.

Durango quickly became home. “It’s such a unique small town,” she says. “The access to the mountains is unreal.” Her first rides were a wake-up call. “I showed up thinking I was a mountain biker and realized I had a lot to learn.”

Her first full-suspension bike, a used Yeti SB95 from a local racer, marked a turning point. She began commuting to the hospital on singletrack, building a life that balanced science and riding. “It was the balance I didn’t know I needed,” she says.

Before Durango, Nichole worked in vascular research, studying biomarkers and blood-thinner strategies for high-risk stroke patients. In Colorado, she transitioned to anatomic pathology, joining a cancer diagnostic team. The same curiosity that drew her to new trails also led her to the Hospitals of East Africa.

After recognizing a systemic disparity in pathology training, Nichole founded Path of Logic. It began with a simple realization: unpaid labor was the most immediate problem. Nichole created the nonprofit to support pathology residents’ salaries, then expanded its mission. When residents asked for help organizing paper records, she saw an opportunity to create real change.

She raised funds, hired a software consultant, and helped build a digital tracking system that dramatically reduced diagnostic turnaround times. What started in one lab spread to five hospitals. “When doctors graduated and moved,” she says, “they wanted the system wherever they went next.”

Nichole describes Path of Logic as a “red tape safety net.” Large global grants fund major initiatives, but rigid rules often leave critical gaps. She recalls a Pfizer grant that allowed tablet rentals, but not purchases. Renting cost more than buying, so she paid for them herself.

Other grants require reimbursement receipts, assuming teams can front costs – often impossible in low-income settings. “These small details,” she says, “are the difference between success and failure.”

Path of Logic’s work has since expanded to include a dissection hood to protect trainees from formaldehyde, a breast biopsy clinic, and a national digital registry.

Nichole later returned to school for data science and public health. Her thesis focused on cancer biology and a new model of health education using animation – data-driven storytelling designed to shift behavior, not just awareness.

Uganda has forty-one living languages, and traditional health messaging doesn’t translate easily. Nichole partnered with Ugandan animators to create a film refined over two years with local women. Humor and familiarity replace fear, making early detection feel possible.

The film is evaluated with pre- and post-surveys, and again a month later, to measure whether it actually changes behavior.

During her early trips to Uganda, Nichole chose to ride solo across the southwest, distributing solar lamps. She navigated rainforest tracks, rolled into villages as the lone “Mzungu,” and experienced moments of real vulnerability – from crashing after startling a monkey to unknowingly staying in a hotel hosting a hostage exchange.

“The bike made people curious in a way no other vehicle ever could, It allowed real interaction instead of observation.”Nicole Baker

Mountain biking became the thread connecting every part of Nichole’s life. What began as avoidance of competition evolved into structured training and racing. “Racing gave me a goal,” she says. Whether riding between rural villages or building medical systems across continents, the approach stays the same: lean into the unknown.

FEATURED BIKE